SPONSORS

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the following sponsors for their generous contributions, which have helped bring this exhibition to life. A special acknowledgment goes to the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art for their invaluable support.

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

- THE EXHIBITION

- EXHIBITION RESOURCES

- SERKONG RINPOCHE

- HISTORY OF TABO

- INTRODUCTION TO TABO

- MAIN TEMPLE: TSUG LHA KHANG

We are delighted to announce the opening on April 10, 2025, of TABO: INTO THE LIGHT, which will feature the oldest Tibetan temple site to survive largely in original form that functions as one of the world’s oldest monastic communities. Famous for its murals, sculptures, and cliff-faced caves, it is popularly known as the “Ajanta of the Himalayas.” Located in the Spiti Valley, Tabo is a small town on the banks of the Spiti River in Himachal Pradesh, at an altitude of 3,280 meters.

Tabo’s main temple, the “Palace of the Excellent Teachings,” (Tsugla Khang) is a unique work of architectural beauty. Dating back to the 11th century, it represents one of the world’s only fully intact arrangements of life-sized sculptures and paintings to depict a three-dimensional mandala.

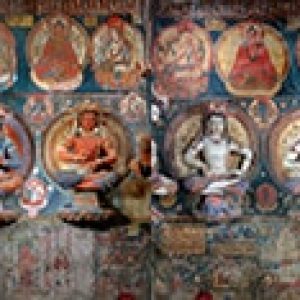

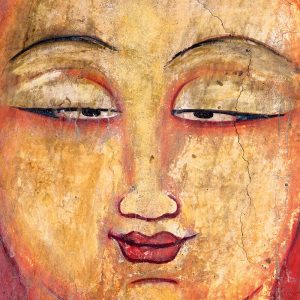

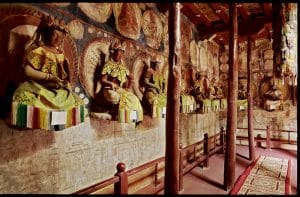

The site’s architectural layout is described in detail in the Vajrasekhara Sutra, an important Buddhist text used in Vajrayana schools of Buddhism. The 32 multi-colored, graceful clay sculptures of Vairochana’s associated deities line the assembly hall walls and are cantilevered out of an attached sculpted halo background. Situated above eye-level, the figures are depicted seemingly detached from their lotus petal appearing to be floating ascendingly. Surrounding these deities on the wall are elaborate, colorful mural paintings—scenes of the pilgrimages of Prince Sudhana (Norzang) and subsequent narrated scenes from Buddha’s life on the lower frieze area.

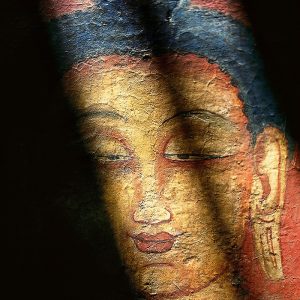

An apse with a circumambulation path extending the Tsugla Khang represents the inner sanctuary of the temple and, next to a pentad of late tenth-century sculptures, features a multitude of life-sized painted Buddhas and Bodhisattvas that rank among the finest depictions in Buddhist art.

Thus in the 90´s of the twentieth century the Indo-Tibetan border regions – both in the Western Himalayas and in the Northeastern hill regions – became second home to Peter van Ham. There he was able to discover and document in depth art, cultures and traditions, which till date had been practically unknown to the Western world.

Eight internationally published books in various editions containing app. 2000 photographs, exhibitions and multivisional slide presentations in the entire German speaking Europe are the fruits borne from his efforts.

His undertakings have been supported by none less than His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet, the Archaeological Survey of India as well as the UNESCO and he has been state guest to various Asian countries.

Photographer Peter van Ham’s high-resolution images vividly capture the intricate details and rich imagery of both the three-dimensional mandala and the ambulatory depictions on the 14-foot gallery walls creating a to-scale replica of the core themes of the Tsugla Khang’s intimate sacred space. This immersive journey intends to deepen the viewer’s perception of being in the temple.

“Entering Tsugla Khang one is deeply awestruck by the peaceful and serene atmosphere that this temple of worship offers. One cannot hold back the impression that divinity is present. This is due to the unified and harmonious design of the big room with its multicolored clay figures, its murals in dominating mineral colors of red and blue and its highly skillfully executed religious paintings of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. The feeling grows that one-thousand years of spiritual power conceived in peaceful meditation still permeates the room´s atmosphere. “

– Peter van Ham

Tsenshap Serkong Rinpoche, spiritual head of Tabo Monastery

Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche is the reincarnation of Tsenshab Serkong Rinpoche, a highly accomplished lama born in Tibet in 1914. In 1948, having received his Geshe Lharampa degree, Tsenshab Serkong Rinpoche was appointed one of the seven tsenshab, or master debate partners to His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. Tsenshab Serkong Rinpoche, who passed away in 1983, served His Holiness in this capacity for the rest of his life and imparted to His Holiness many lineages, initiations and oral transmissions.

The current Tsenshap Serkong Rinpoche (II) – commonly referred to as Tsenshap Serkong Rinpoche – was born at Lari village in Spiti Valley in India in 1984. At the age of six, he commenced his studies at Ganden Jangtse Monastery in South India, and he continued his education at the Institute of Buddhist Dialectics in Dharamsala, where he attained the status of Master of Madhyamika Buddhist Philosophy. After a period studying English in Canada, he is now based in Dharamsala, where he is continuing his studies in higher Buddhist training. He teaches Buddhist philosophy in India and abroad.

Letter from Serkong

Forward by Tsenshap Serkong Rinpoche: spiritual head of Tabo Monastery

Historically, Tabo Monastery is not only famous for its marvelous statues, murals and magnificent shrines, but also stands as a living symbol for the transmission of Buddhism from India to Tibet and the dynamic mingling of various cultures and traditions. Founded by Lha Lama Yeshe Ö in 996, it is one of the most well-preserved Buddhist sites across the Himalayan regions where Buddhism has flourished extensively from the beginning of the seventh century.

Unlike other ancient Buddhist monasteries, Tabo is one of the oldest monasteries that continue to function up to the present, maintaining the traditional Tibetan Buddhist monastic features such as debate, rites and rituals, and all the daily activities of monkhood life. In addition to its historical importance, the monastery also contains the Vajradhatu Mandala, which was reinstalled in 2004 and consecrated by His Holiness the Dalai Lama—a clear indication of the monastery’s vitality and liveliness even in this twenty-first century.

The preservation of such a monastery is important in our modern day not only for its historical value, but also for its significant role in supporting the flourishing of Buddha Dharma, especially now when the situation of Buddhism inside Chinese-occupied Tibet is becoming more critical with each passing year. The Chinese invasion of Tibet has brought Tibetan Buddhism almost to the point of extinction. Through the kindness of His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, the preservation of the sublime Dharma is now firmly in the hands of the monasteries situated outside of Tibet, in free countries like India. Hence, I personally think the publication of the book TABO – Gods of Light will certainly benefit Buddha Dharma in general and particularly Tabo Monastery. I rejoice and appreciate the noble work of Peter van Ham for taking the responsibility to write this remarkable book. May its publication be of benefit to all.

Tsenshap Serkong Tulku, April 22, 2014

In the 1960s, the condition of the monastery and of the village of Tabo was not good. Seeing this situation, two monks – Lama Sonam Tobgye and Lama Sonam Ngödrub (Angrup) – took action, with the aim of preserving Tabo’s heritage. As Tsenshap Serkong Rinpoche, who was the debating partner of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, had previously visited Tabo for two days in 1969, the two monks and the local communities of Tabo, Lari and Poh invited him to come back to Tabo in the early 1970s. He arrived at Tabo in 1973. At a time when transport was very difficult – with horses, yaks and mules being the main means of transport – he spent two months going from village to village to provide teachings. He soon became very respected as a spiritual teacher throughout the Spiti Valley.

In 1976, Tsenshap Serkong Rinpoche appointed Geshe Yeshe Chhodan and Geshe Sonam Wangdui to help revive Buddhist practices in the valley. He himself visited Tabo again in 1979, when he provided teachings in Buddhism, as well as blessings to both fully ordained and novice monks, and again in 1981, when he provided teachings on Tsong Khapa‘s Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Lamrim Chenmo), as well as several initiations, including Yamantaka, Guhyasamaya and Cakrasamvara. Through the collective work of Tsenshap Serkong Rinpoche, Geshe Yeshe Chhodan and Geshe Sonam Wangdui, Tabo again became an active centre for the study and practice of Buddhism for an increasing number of young monks, as well as for the lay people in the surrounding community.

In 1983 and 1996, Tabo Monastery successfully organized the Kalachakra initiation at Tabo, given by His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. Afterward, at the request of His Holiness, Tsenshap Serkong Rinpoche undertook a solitary meditation retreat at Tabo for a month. After completing his meditation, he gave a teaching on The Bodhisattva’s Way of Life (Bodhicaryāvatāra) in the Kalachakra Temple. In 1983, Tsenshap Serkong Rinpoche and Geshe Yeshe Chhodan passed away and the responsibility for the monastery remained solely with Geshe Sonam Wangdui.

It was under the guidance of Geshe Sonam Wangdui that the monks and the villagers conducted the millennium celebration of the monastery’s founding in 1996. Geshe Sonam Wangdui passed away on 11 August 2013.

The responsibility for the spiritual life of Tabo Monastery now rests with Tsenshap Serkong Rinpoche (II), as recognised by His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. Furthermore, on 22 April 2015, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama appointed Khen Rinpoche Tulku Tenzin Kalden as Abbot of Tabo Monastery.

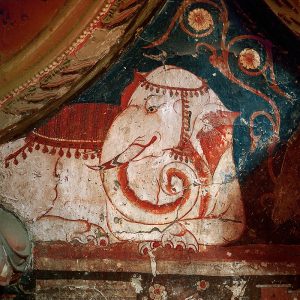

The monastery was founded during the period of the Purang-Guge kingdom (Tibetan: པུ་ཧྲངས་གུ་གེ་) established by Chogyal Yeshe-Ö in AD 967, with Tholing as the capital. Under his reign, Tholing became an important center for Indian scholars to visit and teach. The kingdom also established many trade routes and constructed temples along these routes, in a period known as the second spreading of Buddhism in Tibet (Chidar). The monasteries built during this time – and in particular Tabo, with its location on the route between Tibet and India – were instrumental in the development of Buddhism, and played a significant role in the exchange and debates that took place between scholars and yogis of the Tibetan and Indian Buddhist traditions. The temple complex’ mural and sculptural art also documents local characteristics of the time including non-Buddhist traditions. The oldest monastic establishments of the first diffusion—initiated and carried out by Padmasambhava in the 7th century— such as Samye, were largely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Tabo escaped the brunt of the Chinese invasion and is distinguished by its continuous functioning and role in linking people, cultures, languages, and art during critical periods of Buddhism’s growth and survival. The monastery’s design and decorations are among the most astonishing artistic achievements of the 10th and 11th centuries in the Trans-Himalaya.

In addition to Tabo, the finest extant examples of this style of art can be found in the Alchi Monastery complex in Ladakh, and in the 1,000-year-old Nako Monastery near Tabo in Kinnaur. Central Asian elements, such as rainbow halos, flying dancers, and narrative landscapes, connect Tabo’s art with that found in the Dunhuang Caves, a terminus of the Silk Road in faraway Western China.

The art is a kind of ancient virtual reality, designed as an immersive experience through which one walks: text in the form of wall inscriptions, painting, sculpture, and relief combine as figures that are human scale, three times human scale, and in miniature. Landscapes layer with portraits, and narrative painting with abstract religious symbols. It is a metaphysical head-trip meant to destroy and replace mundane perception with the mental formulations of Buddhist yoga.

Of note, regarding the use of the body in this art, is the seeming weightlessness of the bodhisattvas in relief, and the rare mudra (ritual hand positions) shown, some unidentifiable. In Buddhism, circumambulation, following ancient traces, and walking through mandala temples precede the establishment of dance in India, and lay a foundation for its meaning.

Less spectacular, visually, is the transmission of Sanskrit Buddhist texts and manuscripts that followed their own paths to Tabo, in which the monastery played a crucial role. Not only did Rinchen Zangpo, the “Great Translator (lotsava)”, spend several years at Tabo translating Sanskrit scriptures into Tibetan, but a stream of Indian translators also came to Tabo to learn Tibetan. There, monks ready to teach them collaborated to produce translations of Buddhism’s voluminous literature into Tibetan. These translations were the foundation of Buddhism’s successful second diffusion. Over the centuries, like the artwork that represents the Nyingma, Sakya, Kadampa, and now the Gelugpa teachings, the manuscripts comprising Tabo’s Kangyur, (a set of Buddhist scriptures) are among the most diversely sourced in all Buddhism.

The assembly hall centers on the Vajradhatu mandala, with the main deity, Vairochana, fourfold and larger than life in size. The walls are decorated with exquisite and detailed murals featuring the 32 clay sculptures representing the divine families and realms of Akshobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitabha, and Amoghasiddhi, with Vairochana at the heart of the composition. Continuous painted narrative friezes devoted to the Prince Sudhana’s search for enlightenment and the story of the historic Buddha Shakyamuni are the subjects of the registers below the figural arrangement.

In the passageway extending the temple and leading to an apse and an ambulatory path, a renovation inscription, dated to 1042 A.D., highlights the monastery’s historical significance. These walls are similarly adorned with richly detailed paintings and sculptures: Another fivefold sculptural arrangement devoted to Vairochana occupies the apse of the temple and forms its inner sanctuary. The outer walls of the ambulatory feature altogether forty life-sized depictions: The Seven Buddhas of the Past and the Future Buddha as well as 16 Bodhisattvas and 16 Mahabodhisattvas, some of which may still not be ascribed to any known textual source.